Grid Reference (Without the Grid) - Part 1

Is it possible - or just pointless - to "go analogue" in the wild outdoors?

During recent weeks, my thoughts have turned to doing some detailed planning for walking routes I hope to follow in an upcoming holiday.

During that process, I got to thinking about just how much “getting away” is involved, in this digital age, with “getting away from it all”.

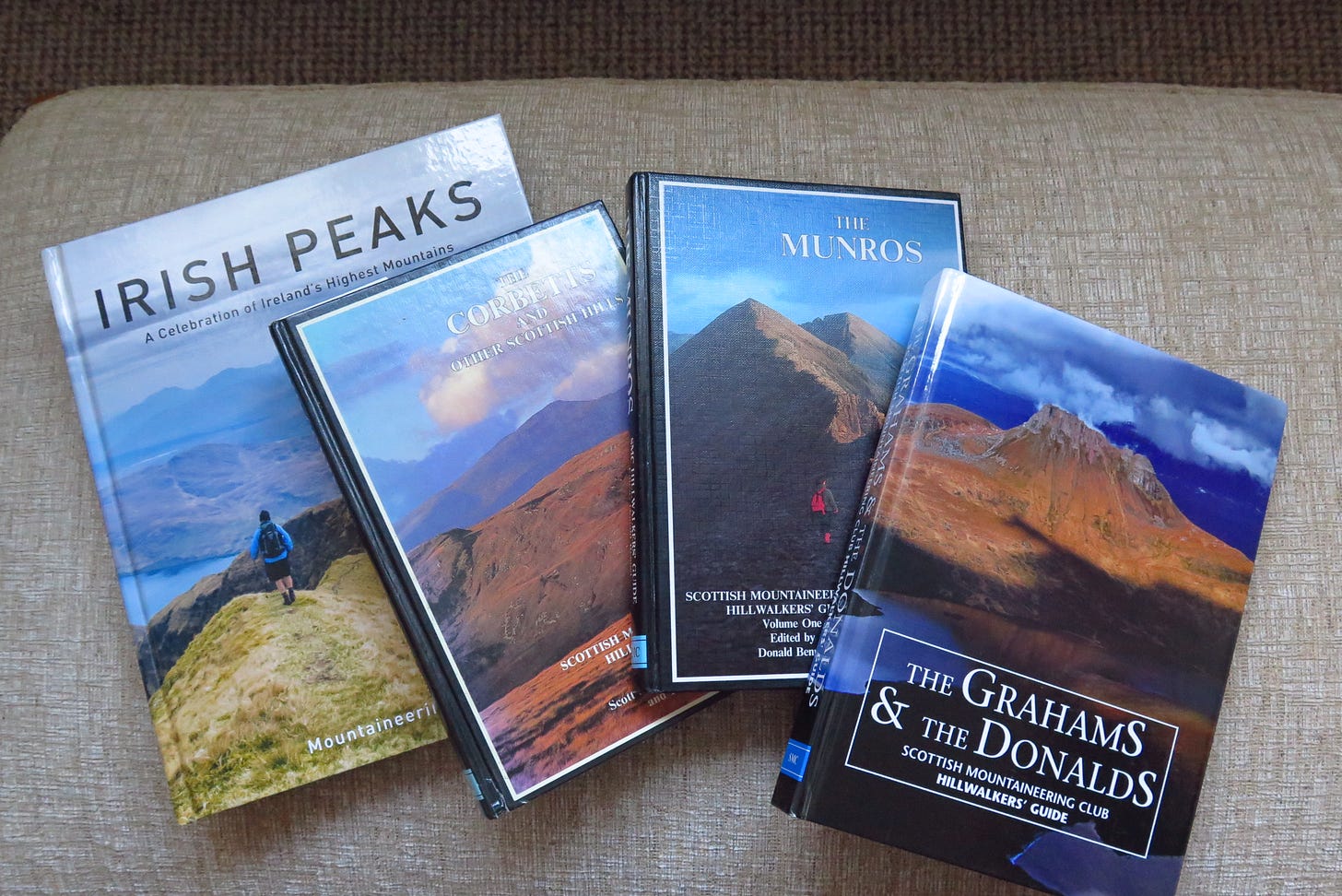

By the Book

These books above contain a huge amount of useful, time-and-labour-saving route and map information packed into their pages, so it seems like all benefit and no real cost (other than the financial investment, which is not insubstantial for these hefty publications).

But the thing is that as long as I have fairly basic map-reading skills, and the relevant map, I can work out the approximate mileage, terrain, total ascent, gradient, and estimated duration by myself.

And although I am as guilty (if that is the word) as anyone else of using the shortcut of the book guide where it is available, I sometimes find that where I am having to start from scratch and plan my own route, there is perhaps more of a sense of adventure in the undertaking, and even a greater sense of personal achievement on the completion of that route. A sense of taking my initial 2D project and bringing it to life as a 3D experience.

Over-Sharing

Even if one doesn’t want to make the investment in the physical books, there is always the free option of going that one more step removed from the fully realised plan, through the use of both official and hobbyist websites where other walkers can upload and describe their own routes.

These sites are often very sophisticated with interactive maps showing trails which are described by contributors elsewhere on the page and other very helpful features.

This option is especially useful as you can look for recent reviews of whichever hills or range you are interested in; so that if there have been drastic changes in access or landscape features (eg a bridge down on the track) you won’t get any nasty surprises when you turn up having probably driven for hours to get to your start point.

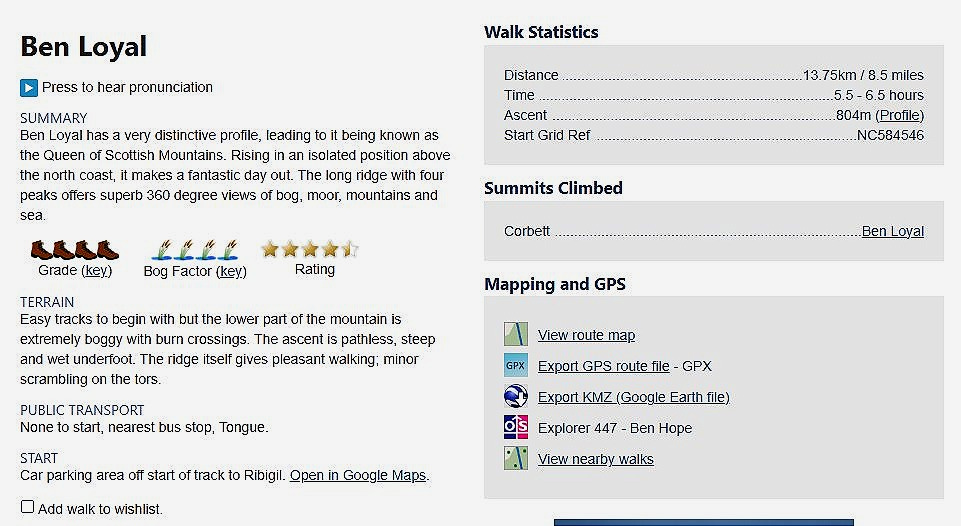

For example here is the main hillwalking reference site for Scotland , where I live.

And this is a typical extract from that website :

So it is clear that a digital reference source does score in that final regard. It is always “live” and (usually) up-to-date. It is not a pay subscription source, and is run by and essentially updated by “amateurs”. That is to say people who are not being paid to maintain the site but simply love their subject and want to share their experience and knowledge with others. Definitely not in any sense incompetent duffers : rather the opposite of that in my view.

So : score one for digital/online planning tools, I have to concede.

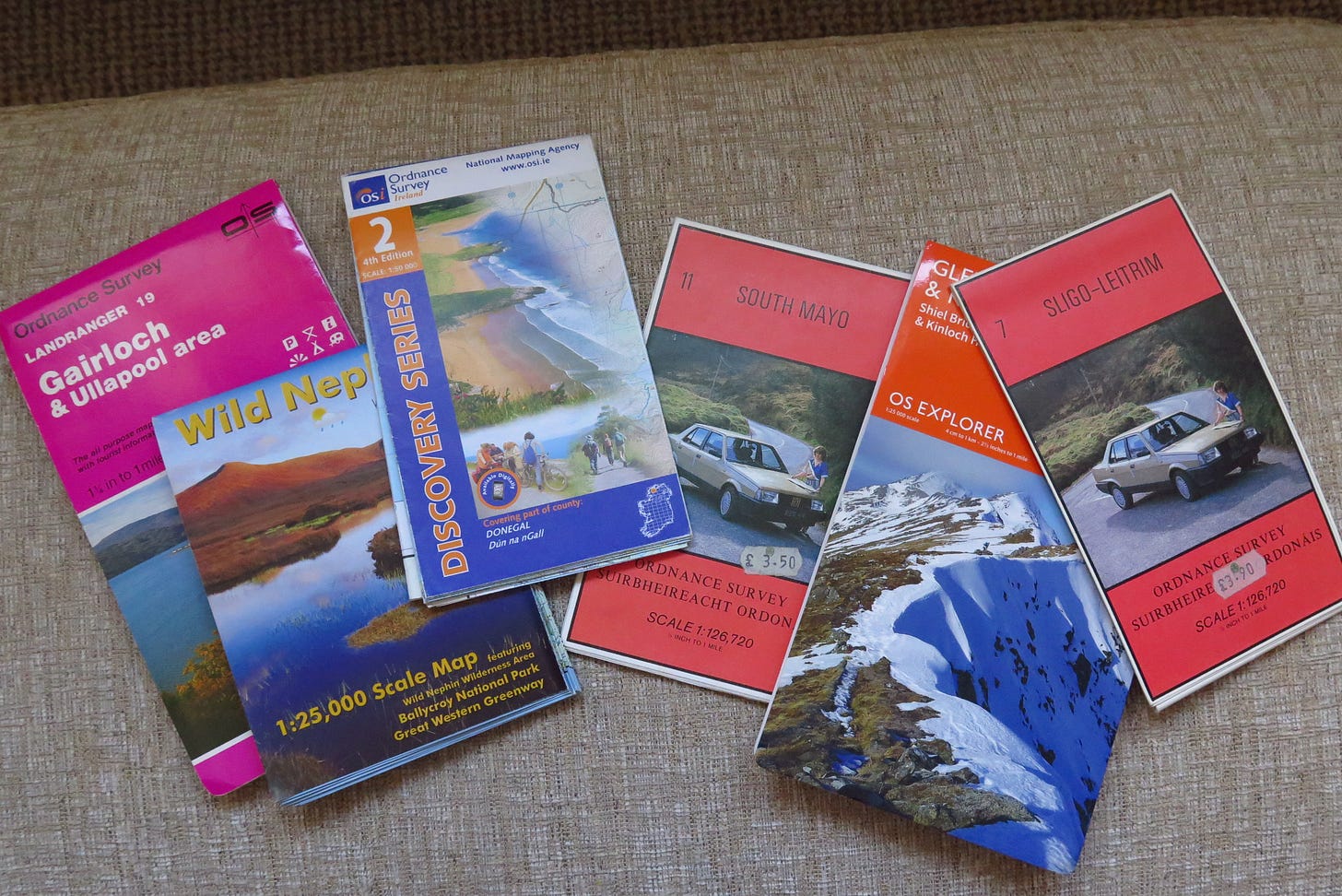

Maps : More is just….more

Let me explain.

When visiting an unfamiliar area with a view to wider exploration, I always begin by investing in the Ordnance Survey walkers’ map(s) for the place. I use the tentative plural there as it is uncanny how often it turns out that a particular feature like a cluster of hills is just not quite covered by the one OS map….necessitating multiple purchases just to be certain that you have it covered completely. Funny that.

I also have a GPS device which displays live map, route(planned) and track(real-time walking record) information. More on that later. But here is where some key distinctions in the analogue/digital comparison appear.

For me, there is a quality as well as quantity distinction in viewing a small screen in my hand as opposed to a couple of square feet of physical map in front of me in its waterproof casing.

Even with an HD display, the ease-of-function difference between scrolling across, down or up to find the feature you are looking for on the GPS’ small screen, and by contrast simply scanning around one square of map paper to achieve the same end, is difficult to over-state.

The latter simply offers a greater understanding of my immediate physical environment, especially when I have used the manual compass to orientate the paper so that I can actually “place” myself “in” the map itself.

The contour lines, gradients and terrain features like marsh, rock, streams and scree slopes come to life on the paper as I begin to identify them in front of me. The map somehow becomes 3D in my head, and scales and distances are as a result better appreciated.

It is literally The Bigger Picture.

On the subject of virtual maps, I have to mention that it seems to be more and more the case these days, with ever-expanding 3G/4G coverage and the ubiquity of mobile phones, that a larger amount of hillwalkers now rely exclusively on this technology.

Of course, it has a lot of convenience advantages which will be a must for a generation of walkers who would never choose the cost and labour (and learning) of maps and compass in preference to a device which they already own and use for so many other things. Why would they?

Well, unfortunately some learn the hard way that total reliance on one option when things don’t go as planned, in a harsh environment a long way from help, is not a good business plan.

Firstly and most predictably, many of the people described above will never have learnt to read a map and use a compass, as they never envisaged needing them for one thing. They have simply (in the vast majority of cases) logged into one of the websites I described above, and downloaded a route file for their intended hike, which they then use for navigation in real time via the 3G/4G network.

To be fair, there are also now options which cater for the time when the mobile signal drops out, by allowing the whole map area to be downloaded before starting.

This then gives some resilience and uses the basic GPS connectivity of the handset to show your position and continue to navigate your path, albeit with some delay and less real-time information. However, in a completely strange environment this is not an ideal situation, especially in poor weather outside of high Summer in, for example, the north of Scotland.

Then there are the real wingers who choose to just rely on using a standard search engine map -itself not nearly detailed enough for the job - and find themselves completely flummoxed when (amazingly enough) they find that they lose cell-phone coverage in the middle of a large mountain wilderness area.

This is exactly what a good friend of mine encountered when she was walking a remote route in the huge and pretty much uninhabited Cairngorms mountain range. The hapless and clueless individual approached her and asked whether she knew the way to [his destination mountain] as it was still too distant to be identified by eye. he had no map, compass, GPS. Just his mobile phone, a useless virtual map and no hope of a signal.

Luckily, it was mid-Summer, fine weather and he had provisions, at least. So she turned him around - he was hopelessly off track - pointed him in the general direction and he went merrily on his way. Much later that day, she did in fact spot him walking back towards the one road in the area, where presumably he had parked, so it worked out okay for him it seems. Fools Rush In, as the song goes.

Coincidentally as I was putting this piece together, this same climbing friend had just returned from a trip to the Highlands, where halfway through a hike of three mountains for the day, the weather completely closed in and she and her partner were subjected to constant heavy rain and very poor visibility for several hours.

They had planned to follow a route which she had downloaded to her mobile phone (so didn’t need 3G as an absolute). However, the rain was such that she couldn’t even hold her phone and see the screen clearly. And of course there was a real risk of water seepage trashing her phone.

So being an experienced climber, she had “just in case” packed the physical Ordnance Survey map of the area in its clear plastic casing, and after managing to take a grid reference before putting the phone away, managed to slowly navigate through the rest of the route by following frequent compass bearings and marking off features as they came upon them, to confirm their exact location as often as possible in the conditions. Then stop, take another bearing and head on again. And so forth until conditions perhaps cleared.

To make matters worse, the several hours of rain had made the task of crossing a stream (which was to be part of the final descent route), completely impossible, as this was now a raging torrent. Such is the speed with which the environment can swing from benign to treacherous in the Highlands.

On that particular subject, this wild unpredictability is under-appreciated by many for one simple but vital oceanic feature: the Gulf Steam or North Atlantic Drift.

The central mountain massif of the Grampians region, as can be confirmed from any world atlas, is on the same latitude (around 57 deg N) as the south of Alaska. If it weren’t for this very fortunate oceanic current configuration - which of course in geological timescales will eventually change - northern Britain, and the British Isles as a whole, would have a very much less hospitable climate.

In fact, the whole Cairngorms mountain range bears the geological, botanical and zoological evidence of a sub-arctic environment in the not-too-distant past, where many species suited to exactly that world live on and thrive to this day.

Reindeer were a self-sustaining population but were finally wiped out by hunters in Victorian times or maybe earlier. They have been re-introduced successfully though, much to the delight of young visitors in December, especially if the snows arrive in time.

To return to my point. Again, in the example above we can see that the paper map was invaluable in picking an alternative route to descend safely - albeit much more laboriously and at greater length - to a point not a huge distance from where my friends wanted to finish.

A perfect and very real example of the value of the traditional approach in challenging situations.

(to be concluded soon in part 2, focusing more on satellite navigation)

Thanks for reading, and I hope you found something of interest whether you are an outdoors type or not. If you did, why not hit that “like” symbol, and of course a “share” or re-stack would be even better if you know someone who might enjoy the piece.

Jim- You’ve captured exactly reasons why I also still prefer paper maps when possible: instant birds-eye view. There’s something about the limitations of the phone screen size that just doesn’t translate the entirety of the geographical scope into memory. I think this is similar to why people sometimes also still prefer a book over kindle. It simply gives us a tangible point of reference to return to. Almost like a landmark during travel or mile marker at minimum. Love maps!

Really good read James. I have always had difficulty reading maps probably because I have difficulty telling left from right. Looking forward to part two.